In June 1944, an unlikely inmate at a federal penitentiary in Minnesota passed the time by corresponding with a priest friend about the wonders and woes of clerical life.

The prisoner was 27-year-old James Farl Powers: "Jim" to close friends and "J.F." to the writers Evelyn Waugh, Donna Tartt and many other devoted fans who gushed about Powers' oft-overlooked fiction as they would, in the words of critic Denis Donoghue, about "an idyllic village in an unfashionable part of France, not to be disclosed to the ordinary camera-flashing tourist."

Powers' first short story collection, Prince of Darkness and Other Stories, was published 75 ago, kicking off a celebrated career dedicated to the messy lives of Catholic priests: their pushy visitors, parish finances, and long, dark nights of the soul.

"The future had assumed the forgotten character of a dream, so that he could not be sure that he had ever truly had one," Powers writes in the bittersweet title story about his main character, Fr. Ernest Burner, whose passions — if ever they had existed — had long since burned off.

Part Willy Loman, part Walter Mitty, Burner is confident he will one day run his own parish. But two decades in, he remains a mere "desperate assistant." When not "brood(ing) upon his failure," Burner imagines himself a star on the links: a "par-shattering padre," he decides, or an advertising guru — or at the very least, someone who can bring himself to face the folded note in his pocket "three days unopened... another letter from his mother."

Alternately comical and sentimental, ironic and poignant, Prince of Darkness, like much of Powers' work, exploits as well as subverts our expectations about men of God and their cloistered lives.

Advertisement

Advertisement

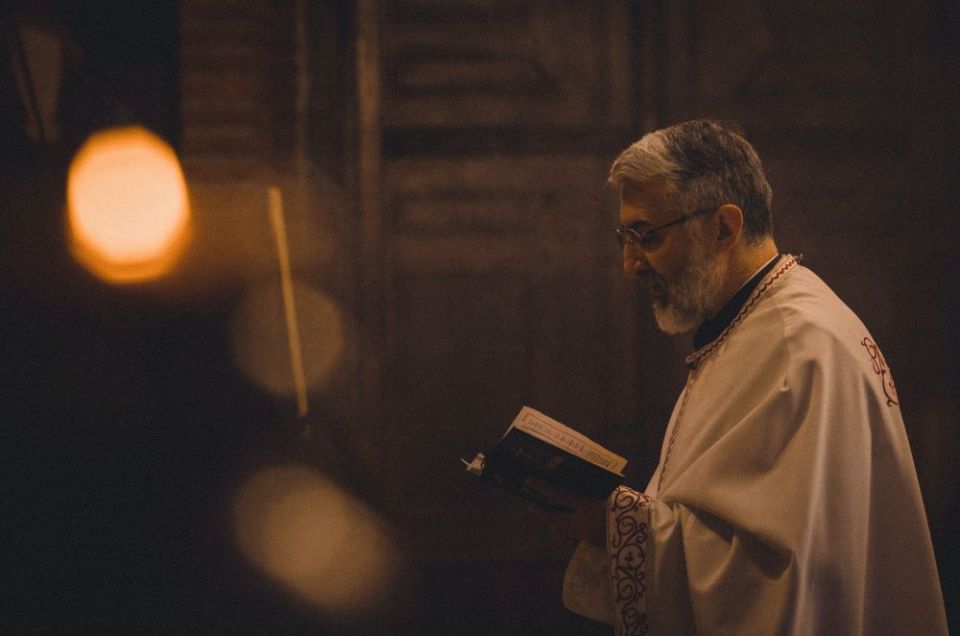

Before Powers, priests were generally depicted as either sinners or saints: the lecherous schemers of 19th century anti-papist tracts, or larger-than-life heroes like Fr. Edward Flanagan in the movie Boys Town. With his episodic portraits on a decidedly human scale, Powers imbued these most Catholic of American Catholics with gnawing doubts, petty grievances and, occasionally, graceful respites from the trials of life.

While Bing Crosby was wooing movie audiences as the suave and witty Fr. O’Malley in Going My Way (1944) and The Bells of St. Mary's (1945), Powers presented readers with a more nuanced worldview. A splash of James Joyce and dash of John Cheever ultimately lent many of Powers' tales what another post-war chronicler of Catholic life, Edwin O’Connor, would call an "edge of sadness."

Born in 1917 to a central Illinois Irish American family, Powers attended a Franciscan high school before enrolling in Northwestern University. He left college to work during the Great Depression, developing a spiritual outlook that was as devout as it was contrarian. So perhaps it is no surprise that as World War II approached, Powers was drawn to the activism and pacifism of Dorothy Day's Catholic Worker movement. He even opposed the military draft, ultimately serving 13 months of a three-year prison sentence as a conscientious objector, where we found him at the introduction of this essay.

Powers eventually split his time between the U.S. and Ireland, struggling to support five children with his wife, Betty, while publishing one new book a decade: a second story collection, The Presence of Grace (1956), the National Book Award-winning novel Morte D’Urban (1962), another story collection, Look How the Fish Live (1975) and one more novel, Wheat the Springeth Green (1988), before dying at age 81 in 1999. A complete story collection edited by Denis Donaghue was published the following year.

Prince of Darkness concludes with a visit from the archbishop. Father Burner delivers all the things he believes his boss wants to hear, hopeful that the long-awaited promotion has finally arrived. What he receives instead is the kind of arresting biblical image we would later associate with Flannery O'Connor.

"I trust in your new appointment," the archbishop tells Burner, "you will find not peace but a sword."

Amidst Powers' own struggles to make a living through art, the author ended up having more than a little in common with his fictional character.

"Jim dwelled on the failure of his own life to pan out as he thought it would and should," his daughter Katherine wrote in a 2013 collection of Powers' letters. "He presented himself as a man struggling — though not always terribly hard — in a world that didn't understand or appreciate him."