4 mural CROP.jpg

I have been reflecting on my part in a long history of the people of Redfern, Australia. I stand on the shoulders of many people — some famous and some unknown — who are important to the mission.

Coming to Redfern in 2002, I joined another Religious of the Sacred Heart, Sr. Patricia Ormesher, and a Daughter of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, Sr. Mary McGowan. Mary had worked with Indigenous people in a remote part of Australia and brought that experience with her, to our benefit. When she and I attended a missiology conference in 2011, she presented a significant paper pleading that Indigenous people be allowed to celebrate the liturgy in a way appropriate to their culture.

We lived in a little house about 10 minutes' walk from the Catholic Church of St. Vincent de Paul, a hub where people gathered to be served, celebrated and mourned. Because of deteriorating health, the pastor, Fr. Ted Kennedy, was gradually withdrawing from ministry, celebrating only a monthly Sunday Mass. Other priests assisted on other Sundays. Ted's sister, Sr. Marnie Kennedy, also a Religious of the Sacred Heart, played a significant role in the community and began a ministry popularly known as street/inner-city retreats.

2 Herscovitch with Mary McGowan CROP.jpg

Our little house was a terrace house (townhouse) where people, mostly Indigenous, would gather. It was a kind of drop-in center where locals came for a yarn, a referral, help with paperwork, a meal, a "cuppa," a food voucher, clothing. Some came for accompaniment to doctors' appointments or court appearances.

One man told me that because of its welcoming atmosphere, chats, and cups of tea, he was able to turn his life around. As an artist, he began signing his paintings with a cup and saucer!

Attending funerals — many for young people who died from violence, accidents, premature illnesses or addictions — was an important, if heart-breaking, part of our ministry.

We didn't run programs ourselves. We were like "first responders," encouraging our friends to engage in programs and courses appropriate to their needs. But most just needed someone to listen, to be accepted, encouraged, and have basic needs met. Building trusting relationships were important.

In the mid-1980s, I attended a weekend retreat where a priest asked the question: "Where will you meet Christ when you go into the city streets?" The question caused me considerable disturbance.

Later, when I heard about the first street retreat in Sydney, I experienced a similar disturbance — signs that something was being asked of me, but I was very much afraid.

In 1987, I came away from a renewal program in missiology, somehow realizing that I would one day live at Redfern, particularly near "The Block," home to many Indigenous people. I had no idea how it would happen and was not in a hurry to do it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Finally, with trepidation, I made one of the street retreats at Redfern. To my surprise, the experience was neither fearful nor disturbing; instead, there were moments of solidarity with those around me, awareness of God in the ordinary, and times of being fully present in the here and now. Following that retreat, I began visiting from time to time.

On moving to our house in Redfern in 2002, I discovered that our "open house" ministry was unpredictable. There were no opening and closing hours, no reception desk — it was just our house, inviting others in. Hospitality ministry challenged me constantly: meeting new people, learning from them and deciding the best response in each situation. I felt a certain loss of control over time, space and response.

I remember one occasion especially. I had invited a couple of sisters to join me for a cuppa at our house. As we engaged in our chat, people began dropping by. All had different needs and wants, but it was the cups of tea or coffee that really mattered, and being together. It felt chaotic and I could have used more than two hands to manage all the requests. But as one of the sisters left, she said something I will never forget: "I could not go to the Eucharist this morning but I feel as though I've had Eucharist here." I was very moved.

1 The Block CROP.jpg

On another occasion — angry about something an Indigenous man had done or said — I expressed real anger toward him, and did not hold back. Later, I feared that because of what I had said he might have harmed himself. I had learned how vulnerable a lot of our people are and how damaging my response might have been. To my relief, however, the next day I did see him again and he held no grudge. I was humbled because another thing I have learned over the years is how forgiving our people are, in spite of the suffering that colonization has brought them.

Another example was a regular visitor who was easily offended by the way I did things, like preparing a sandwich differently from how she would. But she always seemed to forget those "offenses" afterward, and visited frequently.

Another time, a woman asked me for something, and I embarrassed her in front of others by the way I responded. To this day, I cannot remember if I apologized to her. I can only hope so.

3 working on mural CROP VERT.jpg

I have learned many things during these years, but one is very important: to understand that I do not understand, or to know that I do not know, and this applies to all people, but especially to our Indigenous people. Their ancient culture is deep and complex, and no matter how well I think I know them, I realize that there is no way I can fully understand where an Indigenous person is coming from.

The trauma the community has suffered over the years since colonization lives on in their descendants, not to mention the trauma many of them have experienced directly in their own lives — addiction, removal from their families as youngsters, violence in their families, loss of loved ones over and over again, loss of culture and language, loss of dignity, incarceration — and on and on.

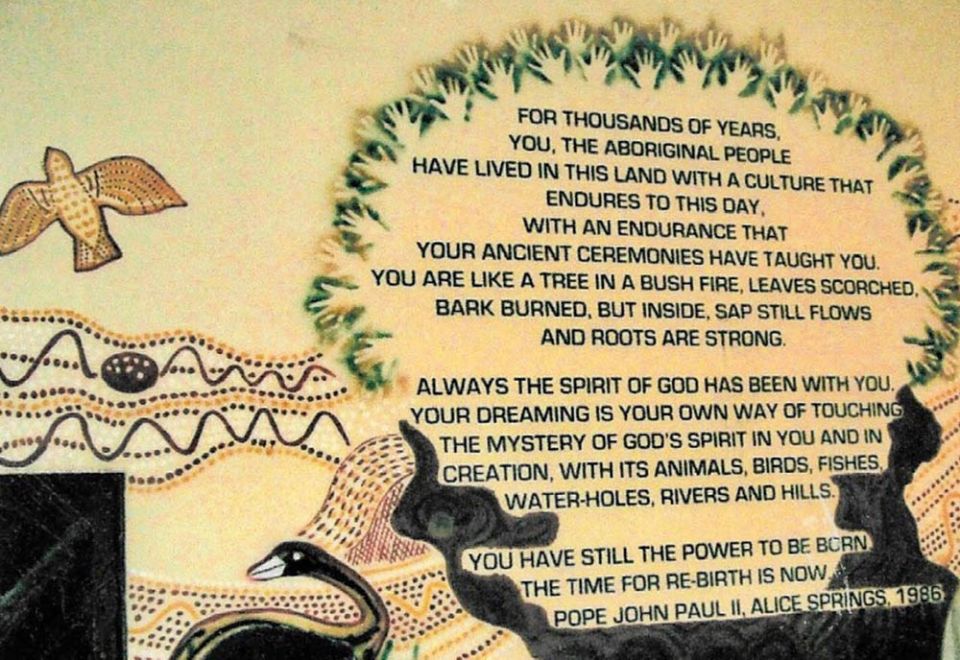

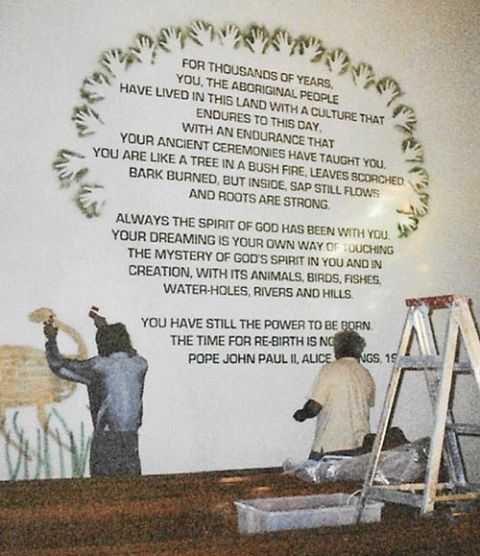

A highlight of my time in Redfern was the communal painting of a mural in St. Vincent's Parish Church, probably more significant to Indigenous people than was our house. The people had decided what words they wanted — those from the speech made by Pope John Paul II at Alice Springs in 1986. Within an outline of a tree and around a few of the words, they painted hands, animals and birds. It is significant to both the local Indigenous people and to the people who have been part of the St. Vincent's Parish over many years.

Although no longer living in Redfern, I remain in touch with the people there and I am involved with a women's group advocating that a "Voice to Parliament" be enshrined in the Australian Constitution. Once enshrined in the Constitution the "Voice" cannot be abolished by the government — as has happened in the past — and would give the right and mechanism for Indigenous people to advise the government on matters that affect them directly.

Like what you're reading? Sign up for GSR e-newsletters!