Valle de Siria, Honduras — Global Sisters Report is focusing a special series on mining and extractive industries and the women religious who work to limit damage and impact on people and the environment, through advocacy, action and policy. Pope Francis last year called for the entire mining sector to undergo "a radical paradigm change." Read more about Honduras mines and activism, including the involvement of Catholic sisters, in earlier stories by J. Malcolm Garcia.

The San Martin mine in the Valle de Siria region of south central Honduras, 90 miles north of the capital city of Tegucigalpa, has been closed since 2009. But its impact on local communities, people living in the area say, continues to this day.

"The San Martin mine is a clear example of the environmental damage and the consequences for human health from mining," said anti-mining activist Pedro Landa. "The devastation is very tangible although it is closed. When the mountains were cut, they left sulfur bank deposits open. With the rains, the sulfur mingles with the rivers and drinking water. People are sick with skin diseases and cancer." In December more than 200 organizations in Latin America wrote a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, calling for greater accountability in Canadian mining operations in their countries. Landa's Fundación ERIC was among the signers.

The legacy of mining operations on health, the environment and social fabric of the community lingers in the area surrounding the San Martin mine region in Honduras, as it does in mining regions across the globe. The economic benefits are largely reaped by others, leaving the cost to the local population. In his encyclical Laudato Si', Pope Francis noted "a true ecological debt exists, particularly between the global north and south, connected to commercial imbalances with effects on the environment, and the disproportionate use of natural resources by certain countries over long periods of time. The export of raw materials to satisfy markets in the industrialized north has caused harm locally, as for example in mercury pollution in gold mining or sulphur dioxide pollution in copper mining."

The responsibility of Canada for abuses related to Canadian mining operations outside the country was a main focus last year of the NGO Mining Working Group at the United Nations, a coalition of nongovernment organizations, most of them religious and including congregations of Catholic sisters. The body focused on Canada, whose human rights record was up for review in 2015 by the Geneva-based U.N. Human Rights Committee. NGO Mining Working Group members submitted documentation to the U.N. panel and members of the group participated in the U.N. review, held in June and July of 2015.

The San Martin mine started production in 2000. In 2006, Goldcorp, a gold producer headquartered in Canada acquired it. Goldcorp operated the mine through its subsidiary Entre Mares during the last three years of production.

"We have put the greatest care into reclaiming the area that was the mine. The open pit areas have been reseeded and reforested, and the land is now being used for cattle and chicken farming, as well as the production of tilapia," a Goldcorp spokesman said.

But some studies say otherwise. In his 2008 report on the mine, Paul Younger, a professor of engineering at the University of Glasgow, found a number of serious problems with the mine: Leakage of cyanide from one of the main storage ponds where cattle graze, and where waters flow to local rivers; signs of substantial physical erosion of one of the principal mine waste management facilities; a flow of acidic water exiting the mine perimeter and entering a nearby river; and exposed pit walls, unrestored and not scheduled for any restoration, which, he said, would remain sources of wind-blown dust and contaminated runoff for decades or even centuries to come.

"It wasn't a minor, temporary, oh-terribly-sorry-kind-of-thing," Younger said of his findings in an interview with Global Sisters Report. "The mine was in no state to be left as it was into perpetuity. A hell of a lot need to be cleaned up before it was no longer a threat to the environment."

The Institute for Environmental Rights in Honduras that the San Martin mine resulted in social conflict and the harassment of environmentalists. It also said affected communities were not consulted or included in any decision-making before and during the mining project as well as in the closing phase.

A Goldcorp spokesman said the company engaged in closure consultations with the community. A closure agreement, he said, was signed with the San Ignacio community. He also said the mine had been carefully observed for environmental integrity.

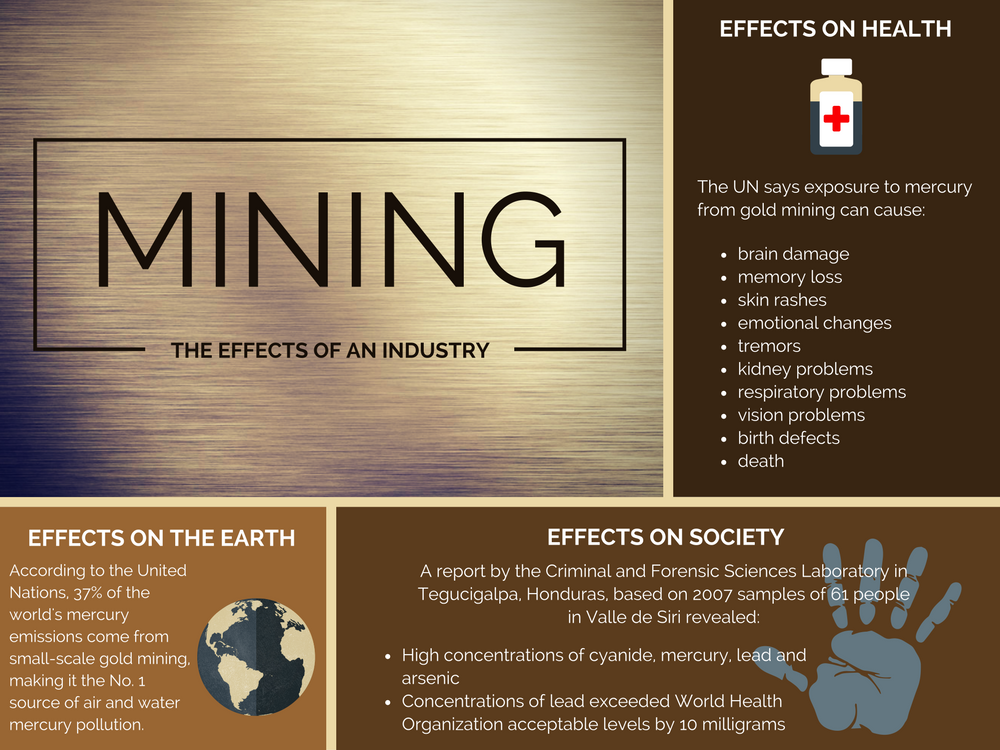

On October 16, 2007, Luis Vidal Ramos Reina, director of forensic medicine at the Criminal and Forensic Sciences Laboratory in Tegucigalpa, released to the government a forensic report on the analysis of blood and urine samples of 61 people in Valle de Siria. Under pressure from environmental advocates the government released information from the report in 2011.

The analysis indicated the presence of high concentrations of cyanide, mercury, lead and arsenic. Furthermore, the report concluded that concentrations of lead exceeded World Health Organization acceptable levels by 10 milligrams. The Ministry of Energy, Natural Resources, Environment and Mines did not return calls requesting an interview for this story.

"Creeks and rivers around the San Martin property have been monitored since the beginning of the operation and after closure by the Honduras Government, all results have shown that the water around the mine have not been impacted by the San Martin mine," the spokesman said in an email. He also said that "mining creates well-paying jobs that allowed our employees and others to feed their families and pay for education and health care."

But the economic benefits of mining in Honduras have come under dispute, said Hugo Noé Pino, an economist with the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies in Guatemala City, a research institute focused on the economies of Central America. The institute found that the contribution of mining to the national economy was modest during the period 2000-2011, Pino said in an interview. The sector contributed on average only 1.25 percent of gross domestic product an average of 6,342 jobs in a nation of 8.2 million.

In terms of tax payments, estimates showed that the payments made by the mining sector in Honduras account for only 10 percent of the nation's tax revenue, he said, well below the 27 percent in Peru, 36 percent in Chile, 37 percent in Colombia and 58 percent in Bolivia.

"I think, in general, the government receives very little from these companies," Pino said. "If you take into account the cost and benefits, Honduras has more social and environmental problems with mining. The problem is in the places where some of these mines have operated, the people there know the problems mines bring. In the cities, there is no awareness of what is happening in these areas."

Valle de Siria continues to be one of these areas. Rodolfo Arteaga had spent his entire life in the town of San Jose Palos Ralos de Siria. Arteaga said he was harassed into selling his land in January 2000 by Glamis Gold, the operator before Goldcorp. He said he was told to move or otherwise the company would get a court order to remove him and he would have to fight to receive payment for his house. He bought land 30 miles away. A farmer, he resumed raising cattle and growing corn and beans.

"In 2007, I needed surgery," said Arteaga, 54. "I had a tumor in my lower intestine. I was found to have high levels of metals in my blood. I still don't feel well."

He said his forced move made him an activist. He now receives death threats because of his opposition to mining.

"I'm tired of fighting," Arteaga said. "Advocacy is a burden."

Olga Noemi Velasquez also lives in Valle de Siria in the town of Siria. Unlike Arteaga, Velasquez did not have to move. But her eldest son, an advocate against the mine, fled to the United States this year to avoid what Velasquez said was harassment by the authorities. Sixteen years old, he was detained and sent to a migrant detention center in Washington, Velasquez said.

"I am very sad," she said. "This has destroyed me emotionally."

The Goldcorp spokesman said he was unaware of death threats or other alleged harassment of mining opponents.

"My wife is always afraid something might happen to me because of my activism," Arteaga said. "When I go out, she prays. When I come back, she gives thanks I am alive.

"My community was lost to an invasion of a few people. The mine is a monster and turned everything upside down. My life as I knew it is over."

[J. Malcolm Garcia is a freelance writer and author of The Khaarijee: A Chronicle of Friendship and War in Kabul, What Wars Leave Behind: The Faceless and the Forgotten. He is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.]

Related - Life-threatening mining is the 'only work' available in Honduras mountains and

Closed mines haunt two towns in Honduras as threats against activists mount