Gray_Whale_Spyhopping_courtesy_of_Marc_Webber_USFWS.jpg

When I was a child, a documentary called "An Inconvenient Truth" warned us of the eventualities of global warming, and how, without fast action, we would destroy our planetary home. My mom took me to see the documentary when it was still in theaters in the mid-2000s, and I watched, horrified, as I was made to believe in the planet's multiple and looming endings.

Nearly two decades after the release of that documentary, we're approaching tipping points, or moments of no return for the climate. This moment approaches us with a question: While we must turn the clock back on our own destruction, can we?

Not can, as in ability, but can as in: Do we have the resolve?

With the memory of "An Inconvenient Truth," I'm brought to a poem from our past that didn't think we could do what we needed to do:

The poem, "For a Coming Extinction" by W.S. Merwin, begins:

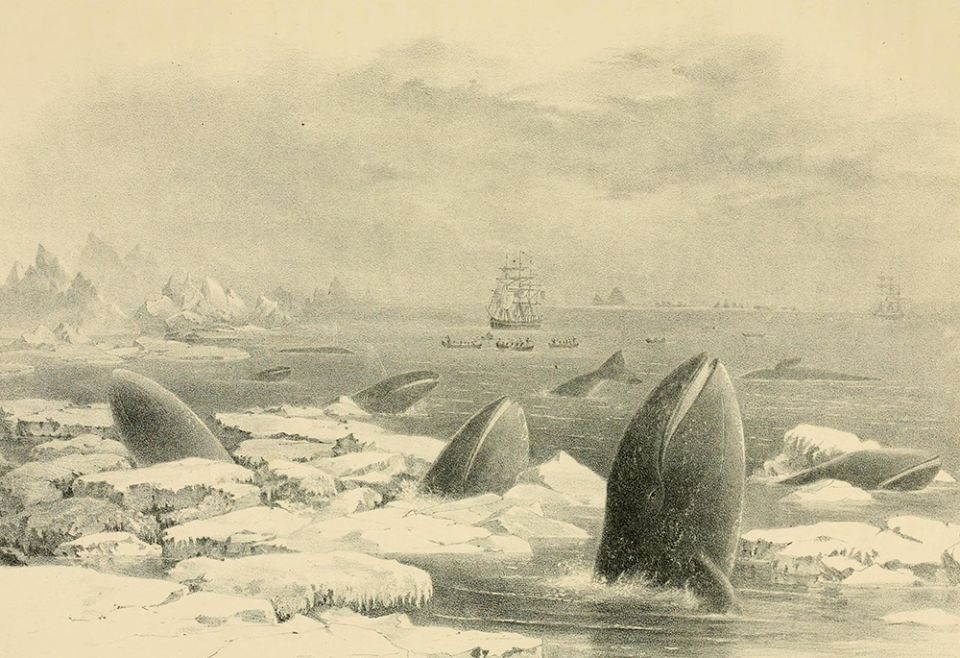

Gray whale

Now that we are sending you to The End

That great god

Tell him

That we who follow you invented forgiveness

And forgive nothing.

The poem was published in 1967, at a time when gray whales were near extinction, their numbers precipitously low — just around 13,000 of them remained after decades of whaling. The 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act offered the sea giant federal protection, which helped the species to launch a comeback and eventually see its removal from the endangered species list in 1994.

But at the time of the poem's writing, the ultimate death of the gray whale seemed inevitable.

Reading Merwin's poem for the first time in 2022, I'm caught by its bleak farewell to the whale species, the casual invocation of God, and the critical tone it takes toward humans and this humanity we've created. Within each of these measurements of life, there are questions of how to say goodbye, who is godly enough to touch the forward side of death, and what magic dies when something that used to exist no longer does.

Advertisement

Advertisement

There are lines in Merwin's poem that appeal to other arrangements of death, not just those of species we rarely directly interact with: "One must always pretend something / Among the dying," he writes, and later: "Leaving behind it the future / Dead / And ours."

How does a future die? What is it we must pretend among the dying? What does departure demand we confront about ourselves, and what happens to us — after the living have crossed over — if we do not complete this task as asked?

In what ways do we die with the dying?

As I read this poem, I imagine Merwin sitting on the beach, notebook in hand, attempting to write a final appeal to God. Writing, possibly, a condemnation for not redirecting those of us humans who take from the earth without giving back, giving way from the destruction of another species. Writing, likely, an apology on behalf of humans for thinking that we could take fate — and life — into our own hands.

I imagine that Merwin looked at the horizon of the ocean and thought that unreachable line was a metaphor for all ecological life, if respected. That life forms and species continue rather than see the point of their own ending, when it is no longer possible for them to reproduce. Extinct.

_California_Grays_Among_the_Ice__-_Eschrichtius_robustus_1874_art_detail,_from-_The_marine_mammals_of_the_north-western_coast_of_North_America_(Plate_V)_BHL16226101_(cropped).jpg

It's easy to see near the end of something and mistake that closeness for the end itself.

Of course, decades after this poem was written, gray whales now are strong in numbers, though not fully recovered to their pre-whaling population count (that will likely never happen) and threats like climate change persist. But a eulogy was not needed for these sea creatures living in what Merwin called the "black garden."

I find that there's a resignation in this poem that can help illuminate the marvelous and deeply alive being that is the gray whale, as well as shine a light on how humans, without intending to harm, can do so in irreversible ways. But on the other side of the gray whales' precipice, I want to read into the poem a message of hope. That's not really how we're supposed to read poems, though, as if they have alternative meanings from what's written on the page.

So I'll offer my own message of hope, or at least, message of meaning-making. Science and data and numbers of dwindling species are not predictive of the future. Instead, they map patterns of past behavior that will prove true if we do not change.

As with the dying, the extinct do not know what has been left behind; it's us, the survivors, creators of extinction, who are left to wrestle with the ghosts of what or who no longer is. We do not always approach The End in ways that we think we will.