SCL Health mass vaccination event CROP.jpg

After 18 months of turmoil, stress and watching COVID-19 victims die, caregivers at Catholic health facilities are reaching their limits.

"With the delta variant and the number of people who have chosen not to get vaccinated, this fourth COVID surge is the worst they've seen," said Brian Reardon, vice president of communications and marketing at the Catholic Health Association, which includes more than 600 hospitals and 1,600 other health facilities in the United States. "The biggest impact is burnout in caregivers and staff. We're hearing multiple reports that they just can't take it anymore."

The majority of Catholic Health Association facilities were founded by or remain sponsored ministries of Catholic sisters. Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, those sisters and other women religious have been working on the front lines, treating the sick and pushing vaccination efforts amid the delta variant's takeover of the country. In addition, they are coping with the ways the coronavirus has affected their lives, communities and ministries.

With more than 41.5 million cases and more than 666,000 deaths in the United States as of Sept. 17, the coronavirus pandemic would strain any health system. But because the delta variant is more than twice as contagious as other variants and millions of Americans have chosen not to be vaccinated, intensive care units around the country are reaching or surpassing capacity.

20210825T1445-HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS-USA-1506961 crop.jpg

In Alabama, there were no ICU beds available as of Sept. 17, and across the South, one in four ICUs were at 95% capacity or higher, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services data compiled by the New York Times.

"It's just been 18 months of unrelenting stress," Reardon said. "This latest surge is now affecting younger people. We're seeing pediatric patients. We're hearing reports of full emergency departments, hospitals resorting to using telehealth and treating people in tents."

Reardon said some Catholic hospitals in Oregon had to bring in National Guard troops to handle basic services such as COVID-19 testing so caregivers could concentrate on treating the sick.

"That speaks to what a disaster this is," he said. "They're facing dire staffing shortages."

But this surge is especially frustrating because it doesn't have to be happening, he added.

"People are in the ICU on ventilators, and it doesn't have to happen," Reardon said. "There's a moral obligation for people to get vaccinated."

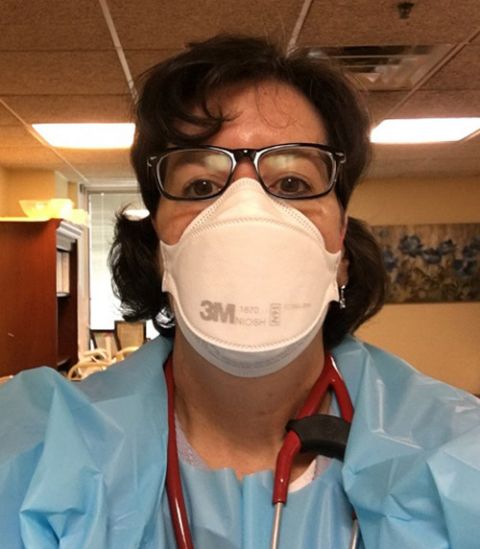

Karen Scheer in PPE CROP.jpg

Mercy Sr. Karen Scheer has seen that up close in her work as a physician with Holy Redeemer Health System in Philadelphia, where she provides primary care to people who are homebound.

"I've lost personal friends, community members and patients to this," she said.

"The biggest tragedy was many families were very hesitant about getting the vaccine, and some gave [COVID-19] to their family members," she said. "Some got sick. Some got better, and some, unfortunately, didn't."

Scheer said the spike in cases is "very disheartening" to see as both a physician and a Sister of Mercy.

"Our primary purpose in life is to live Gospel values and care for one another," she said. "Getting a vaccine can be an inconvenience, but it can be life-saving."

Vaccination lifted Navajo Nation, which covers parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, from one of the most vulnerable parts of the country to one of the safest.

At one point early in the pandemic, Navajo Nation had the highest per-capita infection rate in the country, The Salt Lake Tribune reported. Now, it has one of the country's highest vaccination rates, the Tribune said, and as a result has not seen a huge spike in infections of the delta variant like other areas.

In late August, the Tribune reported that the vaccination rate in Navajo Nation was about 70%, but the rate was climbing as people saw the ravages of the delta variant and wanted the vaccine. Nationally, only 51% of the population was vaccinated at that time. (Experts say 80-90% of the population has to be vaccinated or immune from a previous COVID-19 infection to reach herd immunity.)

One of those responsible for the high vaccination rate on the reservation is Sr. Michelle Woodruff, who for more than a decade worked as a public health nurse at a clinic about two hours northwest of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Woodruff, of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ, ministered to the Navajo Nation until the end of July, when she moved to St. Louis to work in formation.

Michelle Woodruff 2 portrait cc.jpg

"The vaccine push went very well, and we had a great turnout in the beginning," Woodruff said. "One of our counties, McKinley, was around 78% vaccinated [when I left]."

The New York Times reports that 97% of the population in McKinley County, New Mexico, is now fully vaccinated, and more than 99% of those age 12 or older there have received the vaccine. (Vaccines have not yet been approved for children younger than 12.) Between Sept. 2 and Sept. 16, the number of people hospitalized for COVID-19 had only risen 3% in McKinley County.

Meanwhile, Cook County, Illinois, is only 55% vaccinated, and hospitalizations have gone up 15%, the Times reports.

Sr. Stephanie Baliga ministers in Chicago's Humboldt Park neighborhood, which is only 49% vaccinated, and she said that number is unlikely to go higher.

"The neighborhood has had plenty of opportunity to get vaccines," said Baliga, a member of the Franciscans of the Eucharist of Chicago, which runs a food pantry at the Mission of Our Lady of the Angels. "We hosted a clinic ourselves for two months."

She said the low numbers in her neighborhood, the population of which is predominantly Hispanic and Black, appear to be a mix of distrust of the health care system and other factors, such as the fear of side effects.

"Many people of color are suspicious, and understandably so," Scheer said. "In Philadelphia, the Black Doctors Consortium has done a lot to reach out to the communities of color, and it's working. It's providers of color providing care, and that's the greatest witness."

Advertisement

Advertisement

As of Sept. 17, about 180 million people in the United States have been fully vaccinated, according to the Times, about 64% of those age 12 or older.

That's 180 million examples showing the vaccine is safe, Scheer said.

"The most compelling evidence is hundreds of millions of people have gotten [the vaccine]," she said.

Meanwhile, health care officials worry what the burnout of caregivers and staff will do to the industry.

"We're hearing a lot from our members about how concerned they are about not only current workforce issues, but what it's going to mean long-term" if people leave the field because of stress and burnout, Reardon said.

He said there is also concern that because hospitals are full of COVID-19 patients, other things go unchecked: chronic health problems such as diabetes and heart disease, as well as mental health and substance abuse, which the social isolation of the pandemic exacerbated.

"There's a confluence of crises out there, with COVID at the top," Reardon said.

Like what you're reading? Sign up for GSR e-newsletters!