Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam — After communist forces captured Saigon, the capital of a U.S.-backed South Vietnam, on April 30, 1975, more than 1 million Vietnamese were estimated to flee the country. For two decades, they went mainly by sea to Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines, attempting to elude persecution and life under communist rule.

They escaped the country in small, unsafe and crowded boats, and ended up in refugee camps in those countries until they could gain asylum in other places, primarily the United States.

On behalf of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, Sr. Pascale Le Thi Triu of Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul offered legal and social services to thousands of 'boat people,' or refugees, for 25 years in the Philippines, where she studied social work.

Triu worked with Filipino government authorities and church officials to support the helpless, especially women and children.

Global Sisters Report recently interviewed Triu about her work.

GSR: Why did you decide to study in the Philippines?

Sr. Triu: In 1972, I won a scholarship to study for a master's degree in social work in one of three countries — India, the United States or the Philippines — and I chose the last. This Catholic country in Southeast Asia was poor and had cultural factors similar to my native one. I gained valuable experience in community organization and development in the learning environment there.

Did you have opportunities to serve Vietnamese boat people there?

Certainly. When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, I was writing my master's thesis on social work and planned to return home. Some Southeast Asian countries, especially the Philippines, had to welcome hundreds of thousands of boat people who asked for settlement in countries like the United States, Canada, Australia. Among steady flows of Vietnamese refugees, some 3,000 women and children — dependents of Filipino Overseas Workers — landed first in Manila Bay on May 1, 1975. The base is in front of our Santa Isabel College, where I lived. These women and children were classified by the Philippines Immigration Authority as displaced persons.

I decided to stay in the Philippines working as an interpreter for Filipino officials who dealt with the urgent needs of displaced persons and eventually the Vietnamese refugees or boat people.

The majority of those displaced persons had poor education and could not speak English or Filipino, so they could hardly find decent jobs. Their Filipino counterparts were unemployed and the government did not have welfare programs at that time.

We [Daughters of Charity] sisters opened our buildings and institutions for the refugees. With the assistance of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, we inaugurated the Center for Assistance to Displaced Persons on Sept. 1, 1975, to provide pastoral care for the Indochinese refugees. I served as director of the center until all refugees were resettled, and I returned to Vietnam in 1999.

How did the center support Vietnamese women and their children?

Legally, we tried to protect those women against imprisonment because they lived with Filipinos without marriage. Those men worked in Vietnam and had one or more Vietnamese women, although they were already married to Filipinas. As you know, Filipino laws ban unmarried men and women from living together.

We defended the Vietnamese when there were disputes between them and their Filipino relatives. We facilitated the financial support from Filipino fathers to their Vietnamese dependents.

We also worked with Filipino officials to allow Vietnamese women and their children to settle permanently in the country in view of their close affinity with Filipinos. Without resident status, they would have no right to study, to work or to own their dwelling or business properties.

Those who lacked legal conditions for local settlement were introduced to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to resettle in other countries or be voluntarily repatriated later. Regarding welfare services, we provided low-cost housing in Novaliches, Manila, for the displaced persons; for the boat people we established a Viet village in Palawan. These two entities still exist today.

Clothes shops, Vietnamese restaurants and French bakeries were set up from 1978 to 1985, and women were employed to work according to their abilities. One of the restaurants still exists in Palawan.

Through intense advocacy with the government, most women and their children, who had no personal papers, were eventually allowed to enter local schools. The church, through the displaced persons center, provided them with scholarships. Our staff and volunteers also taught them English, Vietnamese and catechism.

Hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese asylum seekers landed in the Philippines for decades. Did you take care of them?

Yes. Large flows of boat people sailed to the Philippines for 20 years, from 1975 to 1995. The U.N. refugee program offered them food, health care and travel expenses, while the local Catholic church gave them basic living supplies. Refugees enjoyed more basic freedoms in the Philippines than those in other countries because Filipinos were very kind and hospitable to them.

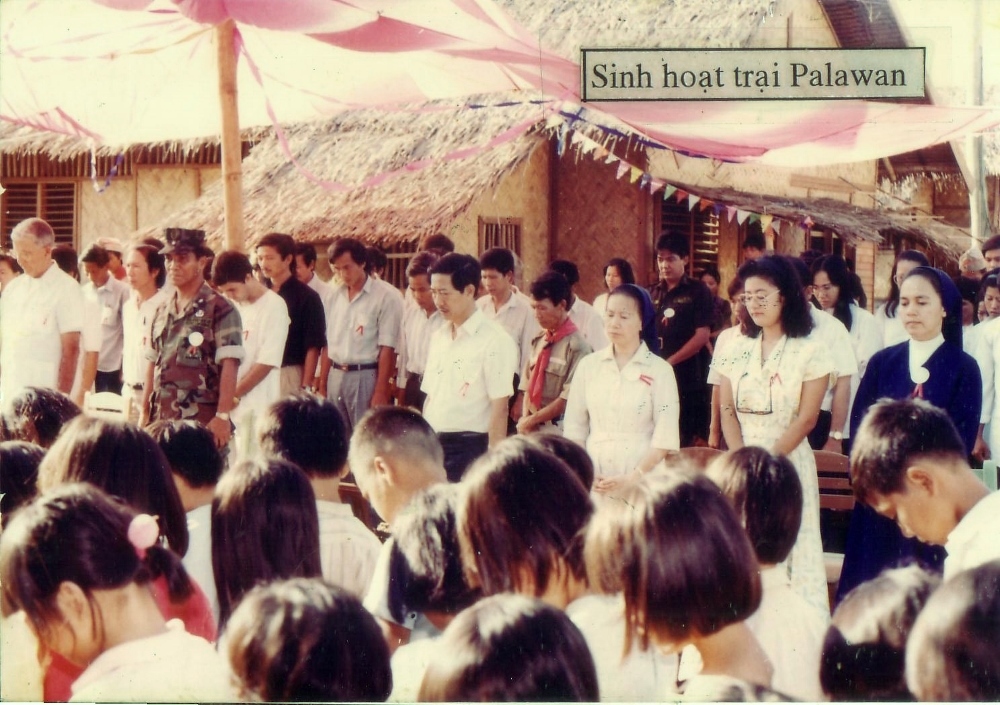

We persuaded military officials to allow the refugee camp in Palawan to have self-governing status. Refugees elected representatives to govern their camp. Their children studied at schools in Vietnamese and were taught by Vietnamese teachers. High school graduates got certificates that would allow them to enter colleges in Vietnam, in case they were repatriated later, or to enroll upon their resettlement in third asylums.

Refugees could attend courses in secretarial work, accounting, computer skills, English and French. They also learned how to cook, bake breads, make Vietnamese-style clothes, and do hairdressing and other trades. They consequently had jobs while living in the various camps and prepared themselves to settle in other countries. The church helped meet their living expenses.

What are the greatest successes?

We protected the helpless and weak refugees against bullies. At times, we had over 500 unaccompanied minors, aged 5 to 17; we organized their lives in family-style clusters with active adults serving as foster parents.

We helped negotiate and foster harmony among different groups of people whose interests might be in conflict with one another in refugee camps that catered to tens of thousands of residents and 2,000 staff from different nations. We also advocated for the refugees to observe their cultural values and rituals, and to have equal access to rented facilities, which were primarily designed for the staff only.

We struggled with various authorities on behalf of the refugees' humanitarian grounds. In 1996, Vietnamese boat people refused to be forcibly repatriated. With the Filipino bishops' support, we persuaded the government to abolish the order. Representatives of the Department of Social Welfare and the displaced persons center signed a memorandum of understanding allowing the boat people to remain living legally in the Philippines until a durable solution could be found.

Thus we built the Viet village in Palawan in 1996. Vietnamese around the world made generous donations to the construction of 200 houses. Refugees spent time building houses, churches, ancestor temples, pagodas, libraries and restaurants. Financial loans for self-employed businesses, bakeries and noodle houses were made available for income-generating purposes. Medical aid and educational grants were also provided.

After the flow of boat people ceased in 1996, a new kind of influx to the Palawan village began: Groups of Vietnamese fishermen, who were arrested by Filipino naval forces for catching fish illegally in Filipino waters, were welcomed there. Thanks to our intervention, they and their boats were released and conducted to international waters to return to Vietnam.

[Joachim Pham is a correspondent for National Catholic Reporter, based in Vietnam.]