• Elise D. García is blogging for GSR from the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, France, Nov. 30-Dec. 11, 2015. Find all the GSR COP21 coverage here.

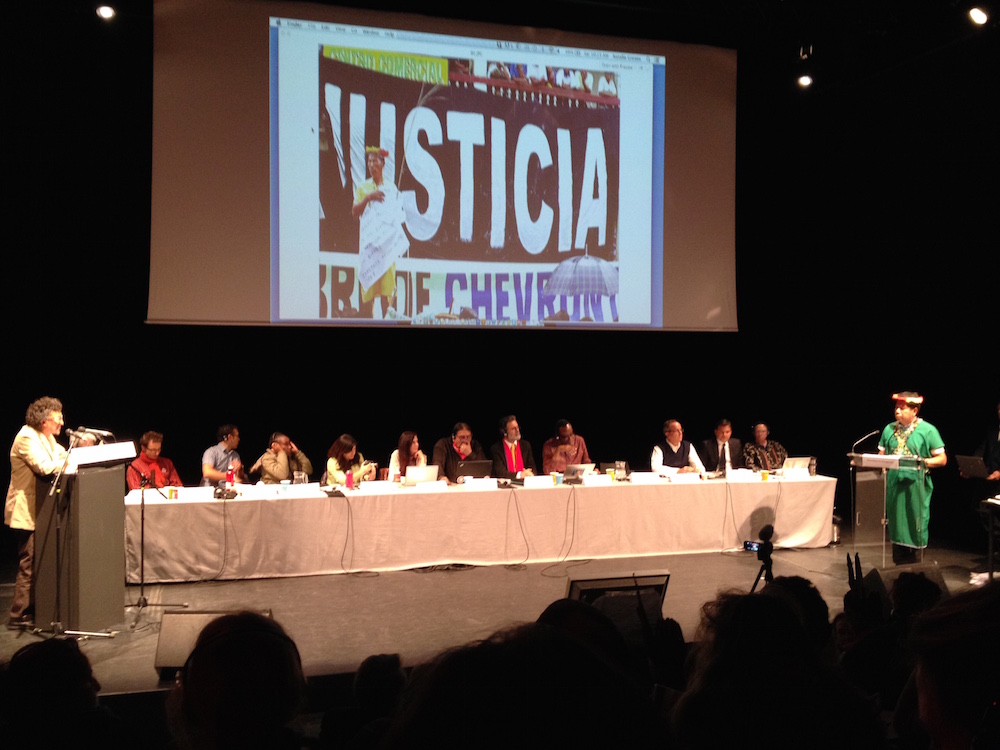

Paris, France — As the second day of the International Tribunal on the Rights of Nature opened in the packed auditorium of Maison des Métallos, a cultural center in the heart of Paris, a disturbing word was shared about the COP21 negotiations taking place just north of the city.

"Some countries are working to remove Proposal 10 today," Ecuadoran Natalia Greene, secretary-general of the tribunal, said. "This is the only provision in the climate agreement that mentions indigenous people, the integrity of ecosystems, and Mother Earth." She asked the 500 or more people attending to help generate a "Twitter storm," urging climate negotiators to retain the language.

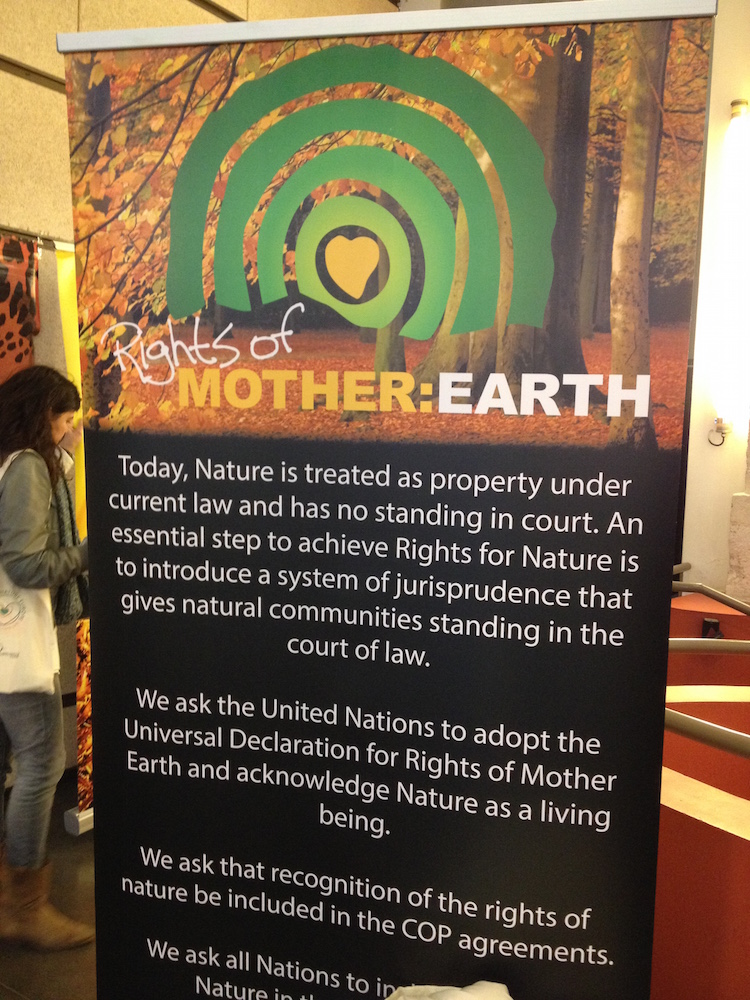

The struggle over that provision illustrates the gap that exists between civil society and COP21 government negotiators over what is needed to keep global warming below catastrophic levels. For civil-society and faith-based groups, the climate agreement must be responsive to the harm done to indigenous people and other communities already experiencing the ravaging impacts of climate change. It must protect the interconnected ecosystems that sustain life on our finite planet. And it must recognize our dependence on Earth and our interdependent relationship with one another and the larger community of life on Earth.

These aims require major economic, legal and social systems change, as reflected in the ubiquitous slogan on banners and posters, "Systems change, not climate change."

For developed nations and corporate interests, the economic bottom line is a key driver — seeking provisions that minimize the costs of mitigation and carbon reduction and maximize opportunities for profit. As a result, the most bandied solutions for addressing climate change at the COP21 negotiations are technology- and market-driven.

The technology-driven schemes sound like Star Wars — engineering volcanic clouds over the arctic to block light and installing thousands of mirrors in space to reflect light, or fertilizing the oceans and genetically engineering plants to create more carbon absorption.

"Even though this sounds like science fiction, it's moving forward quickly," said Silvia Ribeiro, Latin America director for ETC Group, which works globally, monitoring the impacts of new technologies on the world's poorest and most vulnerable people. In testimony before the tribunal on a case involving "Climate Crimes Against Nature," Ribeiro addressed the danger posed by massive technology fixes like these, which promise an untested remedy in the distant future to permit continued carbon polluting today.

These proposals not only provide an excuse for continued polluting, they are extremely dangerous in and of themselves. "There is no way to experiment with a volcanic cloud over the Arctic," Ribeiro said, providing an example. "The only way forward is to implement, and once that’s done, it's irreversible."

The market-driven solutions focus on the financialization of nature. These solutions propose a so-called new "green" economy that reduces nature to the role of a "service provider," as Jutta Kill, a German biologist, described in testimony. Nature's capacity to store carbon and recycle water, for example, would be identified and measured, creating equivalents in a "net zero" scheme where the destruction of a forest in one place is justifiable as long as a forest in another place is saved from destruction.

"It's called 'net' zero, not zero," Kill pointed out. "Please note the big difference that comes from inserting three letters. It makes it possible to continue the damage and pretend that no damage has been done."

In one case after another, heard over two days by an international panel of judges in a "people’s tribunal," testimony like this was brought forward by individuals from all parts of the world concerned about the urgent need for systemic change in our economic and legal structures. The tribunal has no legal authority, but "it speaks with moral authority, representing the voice of the global community of indigenous people and others concerned about the survival of life on our planet," said Adrian Dominican Sr. Patricia Siemen, one of the organizers of the tribunal.

The testimony of more than three-dozen presenters, expert witnesses, and victims of "crimes against nature" documented the systemic ravaging of ecosystems and decimation of vulnerable communities that is taking place across the globe under current law in an extractive global economic system. Even a partial listing of the cases presented is numbing:

- Proposed mega dams threaten to flood vast hectares of Brazil's Amazon rain forest and displace whole communities of indigenous people.

- The extraction of tar sands in Alberta, Canada, is destroying more than 4,400 square miles of boreal forests and the fabric of life of First Nations people.

- Unrestricted industrial and agricultural practices have dried up half the rivers in China since 1990 and are destroying 37 of the world's major groundwater sources.

- Fracking in Oklahoma to extract oil and natural gas from more than 13,000 active wells has made it the earthquake capital of the world. The state went from an average of five earthquakes of 1.5 magnitude a year in 2008 to over 5,000 this year measuring 2.5 to 5.7 in magnitude.

In her closing remarks, Linda Sheehan, JD, co-prosecutor at the International Rights of Nature Tribunal, observed, "There is not one word in the [COP21 climate agreement] about dams, or water, or fossil fuels, or fracking, or even oil."

The draft agreement mentions the Earth only once, in the preamble. In contrast, Sheehan said, the agreement "mentions economics and the economic system 49 times."

By the end of the day, word came that Proposal 10 was still in the COP21 draft agreement. But it remained in brackets, subject to removal.

[Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise D. García is director of communications for her congregation and the former co-director of Santuario Sisterfarm, an ecology center in the Texas Hill Country dedicated to cultivating cultural and biological diversity. Follow her on Twitter: @elisegarciaop.]

Elise D. García is blogging for GSR from the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, France, Nov. 30-Dec. 11, 2015. Find all the GSR COP21 coverage here.